30-06-2022

Scientific Research in China. Collaboration opportunities with UNAM

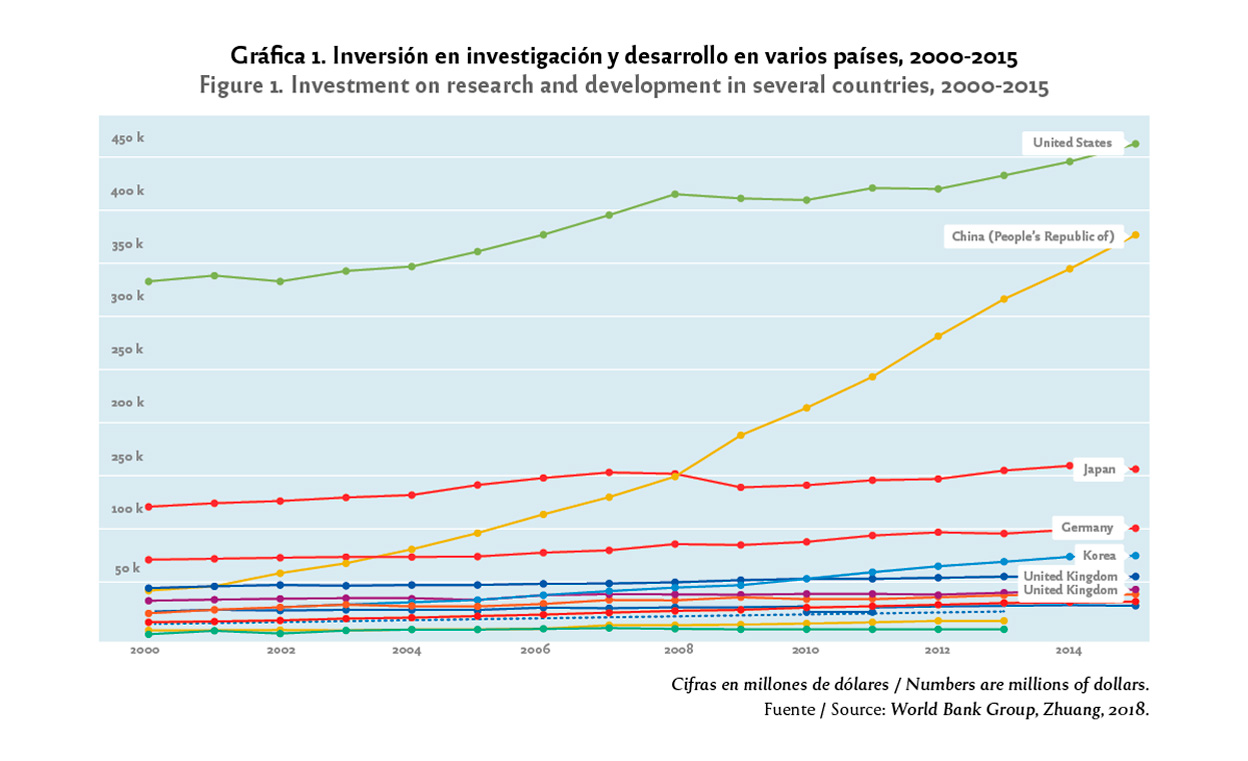

The People’s Republic of China (hereinafter China) began a reform policy and opened to the world in 1978, under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, with the aim of entering into the international market. The new constitution of 1982, the incorporation into the Bretton Woods Agreements in 1987 and the entry to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 laid the foundation for China’s economic take-off and emergence as an economic power.The twenty-first century has witnessed an unprecedented and sustained economic growth: in the first fifteen years, China’s gross domestic product (GDP) grew by an average of 9.5% per annum. As a result, investments in all sectors have increased exponentially. In the case of investment in research and technological development (R &D) in the last eight years, it has maintained a consistent increase of thirty billion dollars (USD) per year. The amount of investment in this area is compared with other countries in Figure 1. It is worth noticing how much China’s R &D investment has grown since 2000. In 2008 the figures surpassed those of Japan and China was placed as the second country with the highest investment level after the United States.

Chinese policy encompasses three lines of action: a) science and technological development integration, b) collaboration research and c) technological enterprises creation. To strengthen this policy, China increased the science and technology budget (S &T) from 1.79 % of GDP in 2011 to 2.13 % in 2017. In this regard, the sector’s five-year plan (2016-2020) indicated that 2.5% of the GDP was going to be invested by 2020 (Zhuang, 2018). According to figures from China’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), it reached 2.4% of the GDP, 0.16 percentage points more than the previous year.

The governing principles of China’s S &T and Innovation policy are oriented to meeting national priority demands, developing cutting-edge technologies, focusing S &T goals on guaranteeing the well-being of the population, d) advancing reforms in the sector, e) developing talent-based innovations, and f) global commitments. The five-year-plan priorities are: information technologies, environmental protection, new materials and biotechnology. In the period up to 2030, the priority sectors are energy and environment, advanced manufacturing, agriculture and biotechnology and space and sea resources. It is worth mentioning the significance of the Belt and Road Global Impact Initiative (See Zhuang, 2018).

THE EMERGENCE OF A SCIENTIFIC POWER

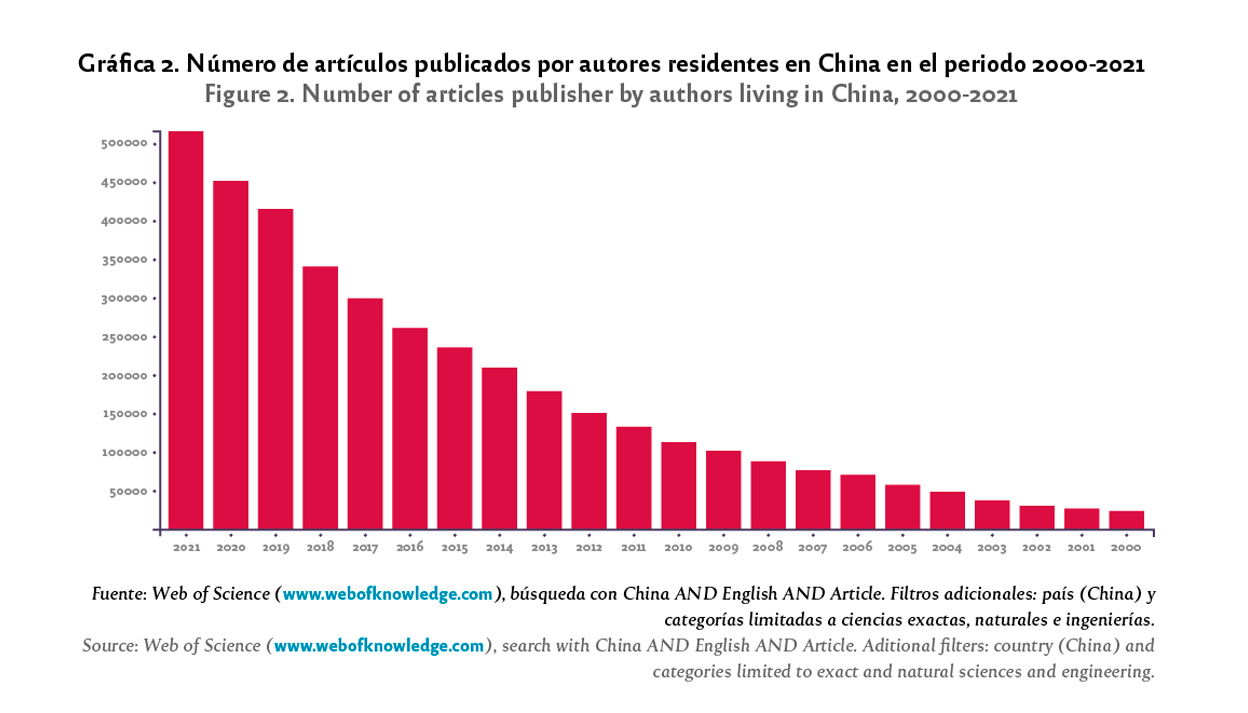

The sound R &D policy in China has brought about major scientific contributions made by universities and research centers. From 1900 to 2019, there were published 3 349 988 scientific reviews (on exact, natural and engineering sciences) according to the Web of Science database (www.webofknowledge.com). In the period 1900-1978, the number of papers was 1281. The coming years from 1979 to 2000, the number increased up to 160 000 out of which 25 715 papers were published in 2000. The following Figure 2 shows the annual output of scientific papers published by authors living in China from 2000 to 2021, a total of 3 872 656 pieces. In 2021, 517 046 papers were published. This growth shows the relation with R &D investment figures shown in Figure 1.

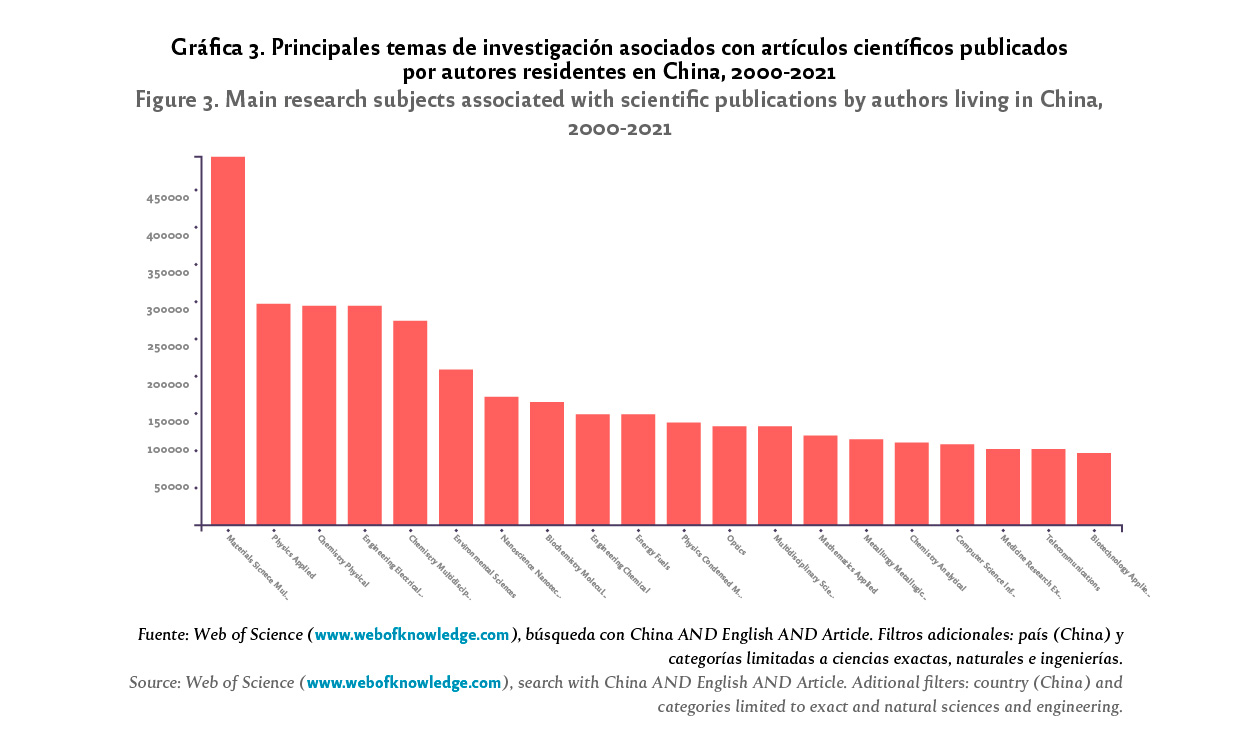

The research topics of most of the papers produced in the period 2000-2021 are shown in Figure 3. Materials science (multidisciplinary) has the largest number, 491 285, followed by applied physics, 295 585, physical chemistry, 29 616, and electrical and electronic engineering, 291 307. Environmental sciences were on the sixth, 207 366 papers.

The growth rate of the number of publications per year shows an overall growing trend, but if subjects are specifically selected, growth trends behave differently. Thus, there is a linear growth of materials science papers (multidisciplinary) during the last eight years, 491 285 as a total out of which 67 846 were published in 2021.

In the case of electrical and electronic engineering related topics, the trend goes down, particularly in the last three years, 291 307 in total for the period from 2000 to 2021 and 45 218 in 2021.

In contrast, papers on environmental science and engineering show a significant growth: the total number of papers for the period 2000-2021 was 239 181 and 49 643 were published in 2021.

CHINA-MEXICO SCIENTIFIC COLLABORATION IN JOINT PUBLICATIONS

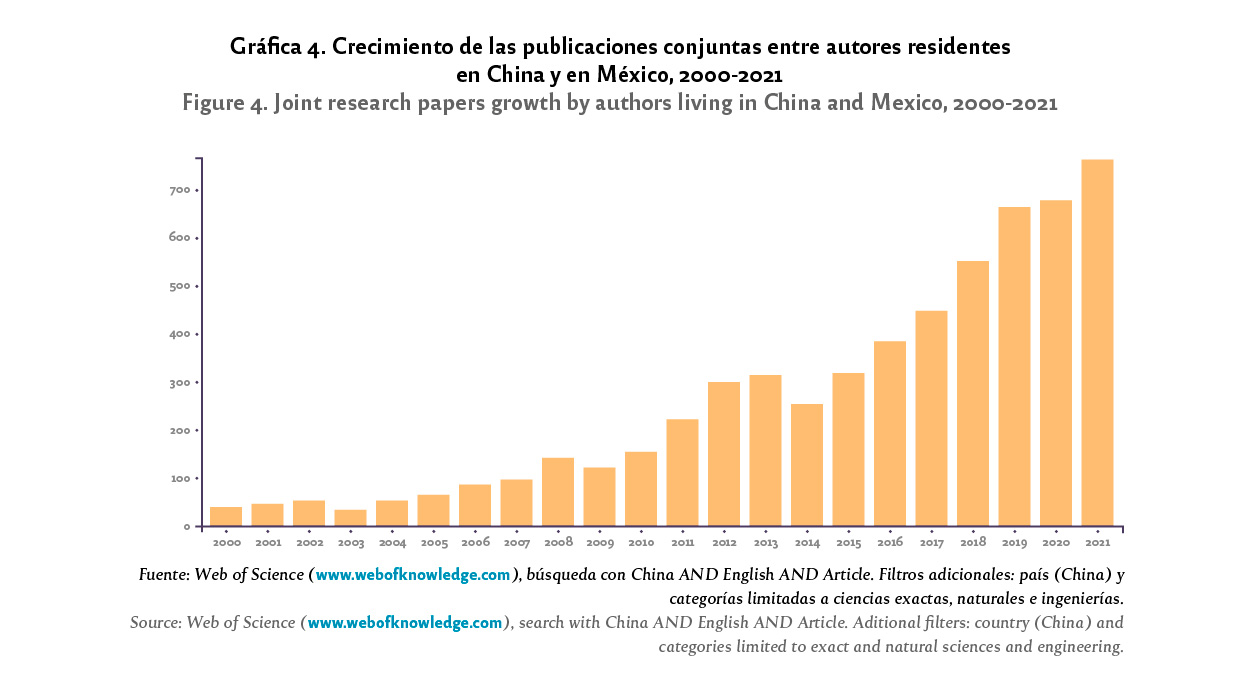

When a search was made in the aforementioned Web of Science database, we found entries for 5849 papers published in co-authorship between China and Mexico researchers during the years 2000 and 2021. The timeline in Figure 4 shows the linear growth experienced during the last eight years; 766 papers were published in 2021.

The main topics of collaboration are field and particle physics, 1538 papers which represents 26% of the total output; astronomy and astrophysics, 1184 papers, 20%; nuclear physics, 644 papers, 11% and multidisciplinary physics, 547 papers, 9%. Mexico-China collaboration is most active in those fields of science that represents 66% of the papers; nevertheless, it is important to add that many of the authors in the above-mentioned fields do publish within large multinational consortia and in multiple-authorship schemes (groups greater than 20 authors and institutions). Figure 5 presents the fifteen most frequent research topics in publications co-authored by Mexico-China.

PAPERS CO-AUTHORED nbsp;BY UNAM AND CHINESE RESEARCHERS

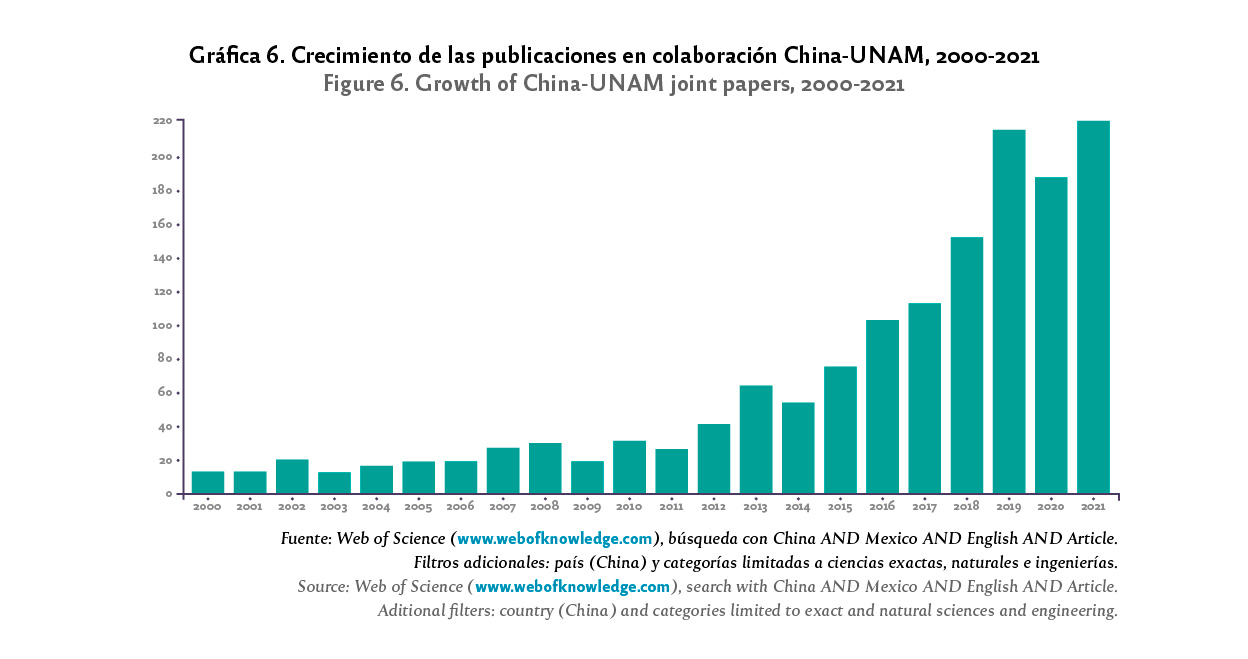

In the referred period, scholars from UNAM produced 1482 papers on exact, natural and engineering sciences out of which 222 were published in 2021 (Figure 6). There is a sustained increase from 55 papers published in 2014, with an unusual decrease in 2020.

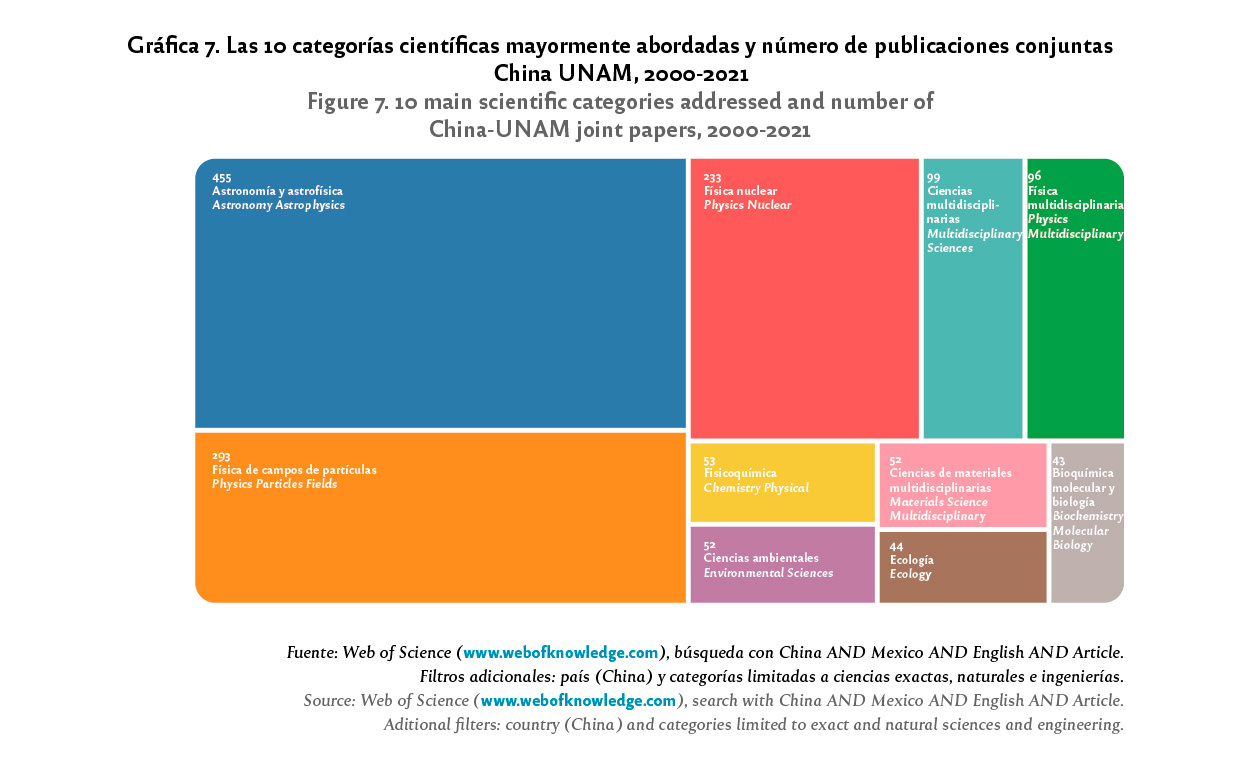

Topics with the highest papers production by China and UNAM scholars are listed in Figure 7. In the same period, astronomy and astrophysics shows the highest amount, 455 papers, that is 31%, then, field and particle physics, 293 papers, 20%, and nuclear physics, 223 papers, 15%. The three categories represent 60% of the papers indexed in the Web of Science resulting from the collaboration among UNAM and China researchers. By choosing the option “research area”, the distribution of co-authored papers fucuses on physics (539 papers, 36%), astronomy and astrophysics (455 papers, 31%), other science and technology-related topics, 113 papers (8%), environmental sciences and ecology (89 papers, 6%) and chemistry (79 papers, 5%). On engineering there are 41 papers that represent 3% of the total joint production in the last twenty-two years.

Taking a more thoughtful look on the areas of collaboration, environmental sciences papers represent 3.5% (that is 52 papers). Within the natural sciences, ecology has the highest record (3%, 44 papers). Within the engineering field, metallurgic is at the top (1%, 15 papers), then electric and electronics engineering (14 papers) and chemistry (13 papers). The distribution by “research areas” shows that engineering and technology related themes have been scarcely addressed in the UNAM-China collaboration efforts. Considering the enormous progress this country has achieved in those areas during the current century, there are great opportunities ahead that UNAM and other Mexican higher-education institutions (HEIs) must take advantage of.

In this regard, the authors of the main Mexican HEIs participating in the 5849 papers published are the National Polytechnical Institute’s (IPN, Spanish initials) Center for Research and Advanced Studies (CINVESTAV, Spanish initials) (2029 papers, 35% of the total), Autonomous University of Puebla (1514 papers, 26%), UNAM (1482 papers, 25%), IPN (1320 papers, 22.6%), Autonomous University of San Luis Potosí (1286 papers, 22%) and Iberoamerican University, Mexico City (1097 papers, 19%).

The information collected in the Web of Science database shows that scientific collaboration between China and Mexico is scarce and it focuses on the fields of physics, astronomy and astrophysics. As it was mentioned, most collaboration projects take place within multinational consortia and, therefore, it does not mean that a direct relationship between researchers from both countries has been established. If the various areas of physics, astronomy and astrophysics are eliminated in the search, the papers published from 2000 to 2021 where Chinese and Mexican authors appeared go down from 5849 to 3138 (50%). The resulting distribution does not show a leading field, the most important is multidisciplinary science and plants science (269 and 268 papers respectively, 9% each), followed by microbiology (243; 8%), environmental sciences (240; 8%), physical chemistry (222; 7%) and agronomy (162; 5%). Within the engineering area, chemistry goes first (144; 4.6) and electrical and electronics afterwards (139; 4.4%).

Therefore, there are great opportunities to increase scientific collaboration with China in the interest of strengthening Mexico’s research and technological development capacity, as well as expanding the training of highly qualified human resources. In this context, UNAM through its venue, the UNAM-China Office for Mexican Studies, can promote collaboration between Mexican scholars and their Chinese counterparts. A recent example is the collaboration established on the engineering master and doctoral degree programs and the engineering and computer science graduate programs with Dongguan University of Technology, China.

COLLABORATION BETWEEN UNAM AND DONGGUAN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY

Dongguan University of Technology (DGUT) was founded in 1992 at the heart of Dongguan City, Guangdong Province (Guangzhou), in Southern China. With the Ministry of Education approval, DGUT enrolled the first university students in 2002 who majored as bachelor graduates four years later, in 2006. In 2003, DGUT created a new campus in the Songshan Lake High-Tech National Park, maintaining the original campus in Guancheng (Dongguan’s downtown). In 2010, DGUT was included among the participating institutions in the Training of Outstanding Engineers national project. Later in the year, the government of Guangdong Province authorized DGUT to award master’s degrees.

Recently, in Guangdong, the Communist Party of China provincial committee and government agreed to invest in five years 3.5 billion yuan (equivalent to 9.5 billion pesos) in becoming DGUT into a high-level science and engineering institution. The goal is that DGUT trains talent student and provides intellectual and technolo-

gical support to the development and innovation project in Guangdong Province and Dongguan City.

Following a long-term planning model, DGUT is preparing engineering doctoral programs that must be approved by the central government. In this regard, to strengthen institutional capacity, DGUT has come up with a strategy to attract doctoral students enrolled in prestigious universities abroad, targeting the first 200 HEIs in the QS World University Ranking. This program is known as the Joint Ph. D Program and it is actually a co-management doctorate program.

DGUT has identified UNAM’s high prestige in the international arena, particularly in the engineering field that placed the Mexican university among the first 100 in the QS World University Ranking in 2021. Consequently, both universities signed a general collaboration agreement in October 2018 while giving the first steps towards the signing of an academic collaboration agreement to create a joint doctoral program in which students would have the opportunity to study in both countries.

Under the joint doctorate model (co-management) UNAM is responsible for carrying out the regular entry and enrollment process of students and issuing the degree when all the requirements are met. DGUT collaborates in the co-management program and provides a two-year scholarship to the students in addition to allow them to use facilities and laboratories. Both tutors and the student agree on the research protocol to be submitted as an enrolment requirement. The agreement is based on a first-year study program at UNAM, the two following years at DGUT and in the fourth year to return to UNAM and Mexico, during which the student must graduate. During the research stay at DGUT, the student presents the semester developments as required by the doctoral program, with the participation of UNAM’s tutor by videoconference.

Before defending their papers, the student must publish jointly with the two tutors an article resulting from their research work to qualify as a quartile 1 (Q1) journal of the Journal Citation Report academic index. The intellectual property produced during the joint doctoral program will correspond to DGUT and UNAM.

CONCLUSIONS

The increase in China’s research and technological development capability over the past twenty years is unprecedented and offers great collaboration opportunities with developing countries. Mexico has sufficient critical mass to increase scientific collaboration with colleagues in the People’s Republic of China, an important strategic aspect to strengthen the sector in our country. However, there is no clear policy in this respect currently.

The analysis of scientific papers by Mexico and China scholars shows that in the last two decades, a growing though small collaboration is making its way through. Papers on physical sciences and astronomy are predominant, 66% of the total amount published during the period 2000-2021. It is important to mention that a considerable number of these papers are produced as part of multinational consortia and, therefore, it does not give a clear picture of the two countries scholars interaction.

The involvement of Mexico and China in engineering and technology issues is scarce. It is clear that there is a wide range of opportunities to increase collaboration, based on the enormous development that China has achieved during the current century. UNAM and other Mexican higher education institutions must adopt policies and allocate resources to take advantage of it.

UNAM, through the China venue, in collaboration with various universities, can promote the link among academics from both countries. A recent example is the collaboration agreement on the Master’s and Doctoral Programs in Engineering, and Postgraduate Programs in Engineering and Computer Science with Dongguan University of Technology for the co-management of doctoral thesis by academics from both universities.

Adalberto Noyola is an environmental engineer from the Autonomous Metropolitan University. He obtained his engineering master and a Ph.D. on wastewater treatment at the National Institute of Applied Sciences in Toulouse, France. Former director and researcher of UNAM Engineering Institute. Actually he is the Director of the Center for Mexican Studies, UNAM.

English version by Zoraida Pérez.

References

Clarivate Analytics (2022). Web of Science (base de datos académica). www.webofknowledge.com

Consejo de Estado de la República Popular China (25 de septiembre de 2021). “China’s spending on R amp;D rises to new high in 2020”. http://english.www.gov.cn/archive/statistics/202109/25/content_WS614eb2e8c6d0df57f98e0d3e.html#:~:text=BEIJING%20%E2%80%94%20China’s%20spending%20on%20research,of%20Statistics%20(NBS)%20showed

Noyola, Alberto (2019). Notas del curso Entendiendo a China. El Colegio de México/UNAM, 10 de agosto a 19 de octubre.

Zhuang, J. (2018). Science, Technology and Innovation Policy amp; International Cooperation in Science and Technology of China (presentación). Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología de China.

English version by Zoraida Pérez.

References

Clarivate Analytics (2022). Web of Science (base de datos académica). www.webofknowledge.com

Consejo de Estado de la República Popular China (25 de septiembre de 2021). “China’s spending on R amp;D rises to new high in 2020”. http://english.www.gov.cn/archive/statistics/202109/25/content_WS614eb2e8c6d0df57f98e0d3e.html#:~:text=BEIJING%20%E2%80%94%20China’s%20spending%20on%20research,of%20Statistics%20(NBS)%20showed

Noyola, Alberto (2019). Notas del curso Entendiendo a China. El Colegio de México/UNAM, 10 de agosto a 19 de octubre.

Zhuang, J. (2018). Science, Technology and Innovation Policy amp; International Cooperation in Science and Technology of China (presentación). Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología de China.