Between guilt and reality. The urgency of protecting the environment

“Separate your trash,” “Don’t use straws,” “Ride a bicycle,” “Don’t travel by plane,” and, “If you really want to reduce your ecological footprint, don’t have children.” These and similar messages have caused many of us to feel a permanent sense of guilt as we go about daily activities such as bathing, dressing, and eating: “How many liters of water did I waste today?” “How many square miles of rainforest were deforested by someone so that I could eat this hamburger?”Many people have chosen to ignore the issue of the environmental crisis on the assumption that it is an exaggeration or a fad; that climate change is a lie. So we ask ourselves, first of all: Is the current alarm over the environmental crisis justified? The categorical answer is yes. A second question we ask ourselves: Can humanity consume natural resources to the maximum without consequences? And here, the answer is no, but it has nuances.

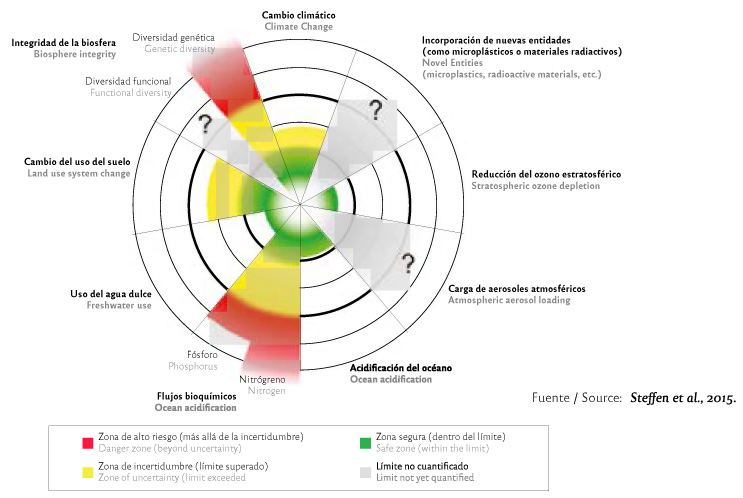

Regarding the alarming nature of the global environmental crisis, we can quote the study by a group of scientists led by Will Steffen (Steffen et al., 2015), according to which four of nine planetary boundaries have been exceeded due to human activities. These limits define the “safe operating space” for humanity, i.e., the conditions that allow the stability of the Earth system in which humans can exist for many generations (see box p. 196). The limits that have been exceeded are biosphere integrity (specifically in terms of genetic diversity), climate change as carbon dioxide concentration in the atmosphere, bio-geochemical cycles (specifically those of phosphorus and nitrogen), and land use system change.

The Planetary Boundary Framework

The planetary boundaries study, published by Will Steffen and a large team of researchers in 2015, defined a series of “boundaries” that, if breached, put the stability of the Earth system, and with it the sustainability of human life and many more, at risk. The graph shows the nine boundaries and their status seven years ago, when the study was published. In 2015 it was still not possible to quantify two of the defined limits: introduction of novel entities (already assessed in more recent studies such as that of Persson et al. 2022) and atmospheric aerosol loading, as well as one of the biosphere’s integrity variables: its functional role. This is how the authors put it:

“The green zone represents the safe operating space, the yellow zone is a zone of uncertainty (increasing risk), and the red zone is already a danger zone. The planetary boundary itself is located at the intersection of the green and yellow zones.”

Based on the planetary boundary framework established by Steffen et al. (2015), another team (Persson et al., 2022) noted that the planetary boundary related to new chemical entities, including plastic, has also been exceeded. In other words, there is cause for alarm.

Let’s go back to the second question: when we hear phrases like “We are destroying life” or “We are the plague of the planet,” who are we talking about? Humanity as a whole? Think, for example, of the ecological footprint with which we estimate the land and sea area required to produce the resources and goods consumed, as well as the area needed to absorb the waste generated, using current technology.

The average ecological footprint of each person is about 6.7 acres, although the planet can only provide each of us with about 4.4 acres. But is the ecological footprint of all humans equal? Obviously not, since average consumption patterns differ significantly from one country to another. An average inhabitant of the United States has an ecological footprint of 20.3 acres, while that of a Mexican is 7.2 and of a Haitian is 1.5.

We can also ask ourselves if the environmental impact of all the inhabitants of the same country is similar. The answer is again no. In a country with severe inequalities as Mexico, if we divide the total number of homes into ten equal parts, one in the top income decile generates more than five times as much carbon dioxide annually as one in the bottom decile. In a country with less inequality, such as France, although there are significant differences in this respect between rich and poor households, the maximum proportion is about twice as much carbon dioxide emitted. Globally, it is estimated that 1% of the wealthiest generate more emissions of this gas than 50% of the poorest.

These figures lead us to reflect about maneuvering space for the people who “weigh” the most on the planet. Clearly, it would be beneficial to reduce their consumption levels. On the contrary, in the case of marginalized people, their consumption needs to be increased to the point of allowing them adequate physical, mental, emotional, and social development.

The questions that arise then are: How can we reduce this environmental impact? can it be achieved by requiring each of the privileged individuals to implement actions in their daily lives such as those mentioned at the beginning? According to Environmentalism, one of the dominant discourses of recent decades, this would be the solution. But Environmentalism conceives society as the sum of the free actions of each individual, which implies that it is not structured or conditioned by a political, economic, and social system. This perspective is criticized as the depoliticization of environmental issues; it is not considered a collective and, consequently, a political phenomenon.

But how does our economic, political, and social system influence the environment? Take capitalism, for example—a system based on private ownership of the means of production, in which the owners of the means of production acquire the labor of workers to produce various goods, whose value produces a profit . One of its objectives is to produce at the lowest possible cost to increase capital. To this end, this system implements production mechanisms that ignore the limits imposed by nature, for example, the carrying capacity of ecosystems.

Even in what is known as “green capitalism” there are disastrous examples since environmentally friendly solutions are generally more costly than those that destroy the environment. One such example is the “carbon market” created to reduce the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. This is how they work: a public authority sets the maximum carbon dioxide emission limit. Each company can emit a maximum, equivalent to a certain number of “carbon quotas” (tons of carbon dioxide). If companies exceed the limit, they must pay the excess. However, the price per quota is not fixed but depends on the fluctuations of the market itself. Because the number of quotas increased excessively, the price of each ton of carbon decreased too much and the operation of this market as an environmental regulator failed.

Phenomena such as planned obsolescence (goods with a short lifetime) and perceived obsolescence (the consumer thinks that the product has gone out of fashion even though it is still functional), closely linked to capitalism, have had disastrous environmental repercussions: excessive energy consumption and serious air, soil, and water pollution, among others.

We could then assume that the solution is to change the economic system, but several researchers have studied the relationship between different economic systems and the environment, and have found that their role in terms of environmental impact is similar. In the specific case of Latin America, left-wing governments have been, like the right-wing ones, largely based on extractivism. Other factors seem to contribute to better environmental management, such as democracy, and human development of the population. Nonetheless, the important thing is to ponder on the root causes of environmental deterioration in order to find real solutions. It is a fact that to protect nature, we urgently need to rethink our production modes.

However, the fact that there are factors that have a greater impact on the environment than individual actions does not mean that we should forget about them. According to a study conducted in France (Dugast & Soyeux, 2019), the daily actions of every French would contribute one-third of the efforts required to comply with the Paris agreements to mitigate the effects of climate change.

It is convenient to carry out actions in our daily lives, but also others with an impact on our community. Thus, some useful actions are decrease our meat consumption, avoid food waste, buy only indispensable products, avoid air travel, but also inform ourselves through reliable sources about the environmental conditions of our community, our country, and the world; use our collective voice to demand transparency from industries about their production mechanisms and make use of networks to inform when industries threaten the environment; in electoral processes, vote for those who have an appropriate environmental agenda; demand transparency and accountability from our governors, and participate in the construction of public policies on environmental issues.

By way of conclusion: the environmental crisis is real and it is urgent to face it. To achieve this, it is necessary, but not sufficient, to implement daily actions. As citizens, we have the responsibility to inform ourselves, to get politically involved, contribute ideas, demand, and inform. As humanity, it is essential to rethink our economic, political, and social systems in order to protect nature. After all, we depend on it for our survival, not the other way around.

Aquiles Negrete Yankelevich studied Biology at UNAM’s School of Sciences, a Master at The University of Edinburgh, UK, and a PhD at the University of Bath, UK. He has taught in grad and postgrad courses in several HEIs in Mexico and the UK. He has worked in both academic and public positions at UNAM, the Statistics and Geography National Institute, the National Commission for Research and Use of Biodiversity, the Institute of Ecology and the Environmental Protection Federal Attorney’s Office. He has published technical articles in books and magazines, both in Mexico and abroad, on Applied Ecology, environmental software, Evolution, and science dissemination and education, an area where he has published several books. Also a fiction writer, he has published short tales in different literature magazines and the book Cuentos comunicantes (UNAM, 2018).

The authors wish to thank UNAM’s DGAPA’s financing, through the PAPIIT program, of the project “SciCOMM narratives for audio-visual production”, without which this work was made possible.

English version by Ángel Mandujano.

Referencias

Dugast, C., & Soyeux, A. (2019). Faire sa part? Pouvoir et responsabilité des individus, des entreprises et de l’État face à l’urgence climatique. Paris: Carbone 4 (https://www.carbone4.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Publication-Carbone-4-Faire-sa-part-pouvoir-responsabilite-climat.pdf).

Persson, L.; Carney Almroth, B. M.; Collins, C. D.; Cornell, S.; De Wit, C. A., Diamond, M. L.; Fantke, P.; … Hauschild, M. Z. (2022). “Outside the Safe Operating Space of the Planetary Boundary for Novel Entities.” Environmental Science & Technology 56(3): 1510-1521 (DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.1c04158).

Steffen, W.; Richardson, K.; Rockström, J.; Cornell, S.; Fetzer, I.; Bennett, E.; Biggs, R.; … Sörlin, S. (2015). “Planetary Boundaries: Guiding Human Development on a Changing Planet.” Science 347(6223) (http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1259855).